Podcast 222 - Static Hiss

/The gang discusses two papers that look at evolutionary changes in animal groups after the End Cretaceous Mass Extinction. The first paper looks at morphometric changes in shark teeth, and the second paper studies the evolutionary and biogeographic patterns of snakes. Meanwhile, Amanda “fixes” her audio, Curt goes biblical, and James is missing.

Up-Goer Five (Curt Edition):

Our friends talk about things that lived through a real bad time when a huge rock hit the big round place where we all live. The first paper looks at large angry animals that move through water and have pointed things in their mouths and soft bits where things have hard bits. We usually just find the hard pointed bits from the mouth because the rest of the body falls to bits when they die. So this looks at how these old hard bits change from before and after the big rock hit. What they found was that changes happened within groups, where some groups were hit hard and others were not. But if you look at all of the big angry animals, it looks like very little changes. The hard bits are doing things that look the same before and after the rock hit, but its different groups doing that.

The second paper looks at animals with no legs and looked at changes in where they live and how quickly they change over time. The paper finds that after the big rock hit, one group was able to move to a new place. This move seems to happen when they also start making more of themselves. It seems that, for this big group of animals with no legs, the big rock hitting may have helped this group. It seems like a new place opened up after the big rock and the group took over and did well. There are also changes that we see when it gets colder in the time way after the rock hit.

References:

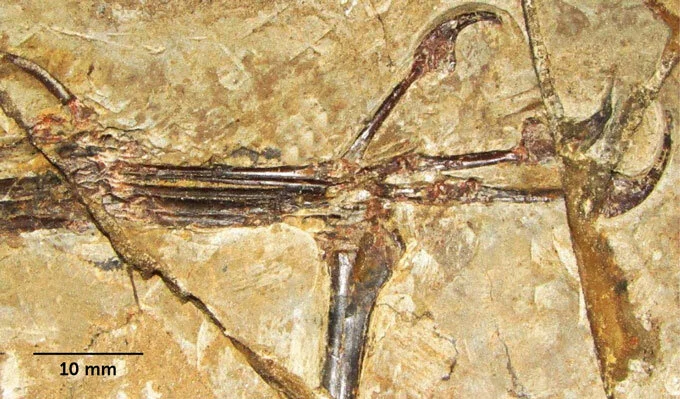

Klein, Catherine G., et al. "Evolution and dispersal of snakes across the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction." Nature Communications 12.1 (2021): 1-9.

Bazzi, Mohamad, et al. "Tooth morphology elucidates shark evolution across the end-Cretaceous mass extinction." PLoS biology 19.8 (2021): e3001108.